The dirtbag zen of Steve Jobs

This story does not begin in Silicon Valley but in the Japanese attempt, 150 years ago, to react to and deal with Western imperialism, which was becoming increasingly inevitable and particularly frightening in a culture with such a xenophobic tradition. At the end of the 19th century, during what is known in Japan as the Meiji era, Japanese academia, for the sake of survival, decided to turn its attention to Western philosophy, particularly German philosophy, with obviously disastrous consequences for the whole world.

When I met a German Zen master at a Brazilian Zen Center, the jokes in the community oftern came to be about the racial stereotypes combined in her. After all, both the Japanese and Germans are often characterized as precise, determined, and serious—quite the opposite of the stereotyped Brazilian. Although the image of Zen in the West is also one of peace and spontaneity, values such as cleanliness, order, simplicity, as well as determination and precision are often at the root of what someone seeking Zen as a practice is looking for—even if these stereotypes reflect only certain aspects of Zen and Japanese culture.

Since I myself have a somewhat germanic appearance and mostly european genetics, while living in southern Brazil, I have often found myself in the unfortunate situation of sitting at a table with a bunch of “ersatz germanics” glorifying Teutonic capability, the quality of German industry, and so on. Often, this conversation is interspersed with clear racist tones, and on one or two occasions, even nostalgia for the Third Reich. Never so openly confessed, but enough to probe whether I would also participate in some kind of Uber Alles.

Up to that point, it was more or less okay—okay in the sense that no one is exempt from their share, even if inadvertent, of racism, regardless of ethnicity, and there are yokels and uneducated people everywhere—not just among Brazilians who like the idea of thinking they are Germans.

The problem is that darn Hegel.

Even if you consider Popper’s assessment of Hegel as a Nazi unfair or flawed, it is certain that the philosopher represents the pinnacle of a certain German culture—which, not many decades later, for reasons that no one who participated in that culture can be entirely exempt from, would result in what it resulted in. The issue here is not so much to point fingers but to precisely delineate what went so wrong in German thought. The problem with obscurantist authors—who write in a complicated manner—is that they can exactly be accused even of things we are not entirely sure they asserted. Accused in the sense of a genealogy of ideas, of course.

Evidently, from a psychosocial perspective, the tribal God of the Jews is an expression of ethnic unity, and perhaps more than that in social terms. When this same God is offered to the Gentiles by Paul, it initially creates some problems—tensions in the traditional structure linked to this God, namely the Temple of Solomon. And just as we have difficulty separating ethnicity from culture in the case of Jews, the same is increasingly true today with Muslims—who, in principle, should be seen as multi-ethnic, like Christians, but often are not. The “German” spirit of the late 19th century was not only not German but effectively contaminated the Japanese—and it’s not as if they didn’t have their own predispositions.

Ethnicity and culture are indeed somewhat inseparable, but then comes Hegel to reify this so-called “spirit of history”—and nationalism, which he may not have glorified so much (explicitly not, implicitly undoubtedly), resulted in what it resulted in.

And let’s not imagine that this is an inconsequential step. There is a tendency in Western thought to insulate thinkers from the consequences of what they thought, and therefore, if Hitler adored Nietzsche, it was certainly some misunderstanding, or the racist editing by his sister, and so on. Nazism is seen (and projected itself) as organic, not intellectual: never as a byproduct of distortions in German education, and never linked to the thought of so many German thinkers that no one is ashamed to have on their bookshelf.

And it’s not as if Hegel’s opponents are without their share of responsibility in what happened shortly after: it was, of course, a combination of multicausal factors. No one is exempt.

Still, it must be emphasized: those “root” ideologues and propagandists of Aryan superiority did not come out of nowhere. They are not the “banalized evil” that adventitiously presents itself in the world. They were also obvious products of their culture.

So much so that Japan went through the same process, through the means of, more or less, the same thinkers!

From this, we can ask whether something of Japanese culture also penetrated Europe at the beginning of the 20th century and, mixing with the spirit of the time, deeply intensified the poison of nationalism, the reification of ethnic spirit, and the capacity to impassively and indifferently inflict an ocean of pain on objectified enemies, with high efficiency.

Romanticism, Japanese Style

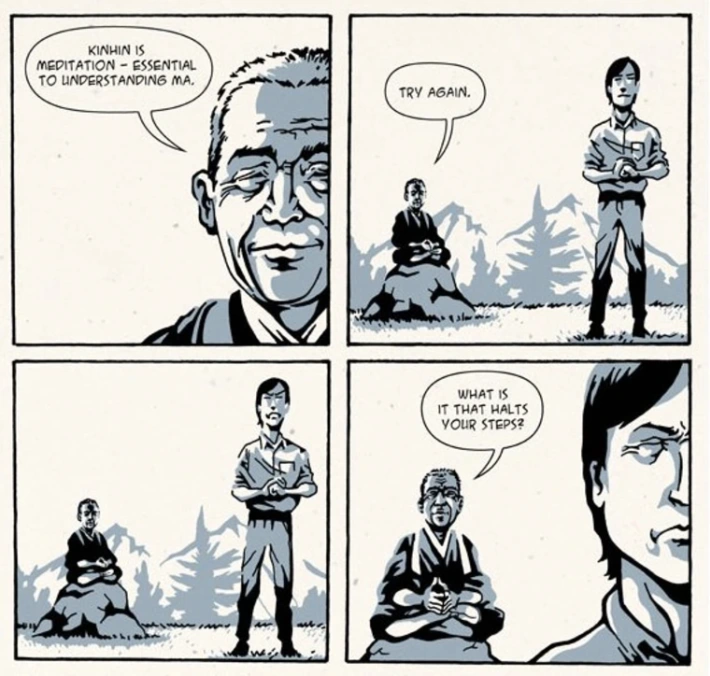

“Zen” is a corruption of the Chinese term “C’han,” which in turn is a corruption of the Sanskrit term “dhyana” (which has a counterpart in an ancient language relatively close to what the historical Buddha spoke, Pali, “jana”). Dhyana means meditative absorption or concentration.

When Buddhism moved from India to China, the emphasis on this practice and these teachings named the main group of traditions that predominated there for some time, and which, along with other schools, eventually penetrated Japan around the year 1000. In Japan, Zen went through successive periods and reforms, establishing dozens of monasteries with their own styles. The most relevant development of Zen in Japan occurred when the Japanese master Dogen Zenji returned from China in 1227 and established a form of practice even more radically centered on the meditation of “just sitting” than what was common, at least publicly, in China and Japan until then.

Dogen established an extremely successful form of Buddhism that survived successive attacks from other established Buddhist traditions in Japan and ended up shaping much of classical Japanese aesthetics, centered on simplicity, and the fresh and direct nature of experience. Spontaneous poetry and unpretentious themes in art—wabi-sabi, the beauty of patina and imperfect, well-worn things, are elements that delicately express dhyana in everyday life.

The pinnacle of Zen aesthetics is the tea ceremony, an elaborate ritual form of socializing and frugal conversation amid art (ceramics, flower arrangement, sewing, architecture) and a form of “living poetry,” where tradition and common life meet. To the same extent that the formality and “rules” of a meeting between student and master, between students, or between masters are traditionally extreme and detailed, the ability to express spiritual realization amid trivial activity is a hallmark of Zen.

All the preparation and pomp—which came to include building a specific place for the ceremony, decorating it, buying or making ceramics, clothes, flower arrangements, etc.—had to remain absolutely implicit. Zen aesthetics despises ostentation. While it does not shy away from refinement and sophistication, the grace of the thing lies in revealing the profound in the least salient—even in the frivolous or irrelevant. Amid all the preparation, all the ritual learning, one must welcome the guest without any apparent effort and without any notion that this involves any kind of personal achievement, whether in the form of the objects (they charm through simplicity) or in the mastery of meditation and the delicacy of the tea presentation.

This is indeed a type of spiritual and artistic expression that was completely alien to Europe at the time, where social customs were deeply dissociated from the spiritual vision, which belonged to the moment of prayer or the Church.

While the Japanese focused on the beauty of not showing off, the Renaissance gave rise to the Baroque in Europe—the exact opposite. The Baroque was a “forevermore” of details to rub in the guests’ faces how much money and labor time had been invested. When the Baroque got tired, the Classical emerged, now with more restrained elaboration but no less ostentatious—and then finally romanticism.

During all this time, Asia was already a cultural reality for Europeans. The Baroque imported Chinese porcelain, and when it went out of fashion, the Classical deliberately ignored (left out of fashion) Asia and turned to the Greco-Roman past of the West. Asia returns with force in the Romantic period, which effectively encounters Zen, and, believe it or not, it is precisely this seemingly bizarre combination of young, idealistic, and energetic individuals and the superficial-made-profound experience of the tea ceremony that will explode in the Great Wars of the 20th century, particularly the second.

The Art of War

Martial arts fans will tell you that they originated as a personal self-defense movement among certain monks in China. Neither India nor Tibet—other countries where Buddhism was central for a long time—developed martial arts; this was a particularly Chinese phenomenon, as any Kung Fu Panda movie can attest.

When Ch’an attempted to enter Tibet, a public debate took place, and the Chinese master seemed to advocate (or so the Tibetans understood) a spiritual path beyond ethics—since in meditation, there are no good thoughts to pursue or bad ones to avoid. The debate was lost—or, cynically speaking, the Tibetan government obviously found that doctrine dangerous—and did not allow Ch’an to enter Tibet.

But, in fact, all forms of Buddhism will clarify that realization is beyond fabricated morality—and some will even say that reality is ethical, and therefore, a Buddha is ethical without any effort, simply by recognizing and being integrated with reality through wisdom. It’s obvious that a Buddha doesn’t follow rules; he or she is a complete expression of freedom—and yet never harms any being whatsoever, and always ceaselessly practices virtue.

However, it’s easy to confuse this “non-conceptual” freedom with a free pass, particularly if a series of self-deceptions overlap and you start believing you’re a big deal, a realized being, and that everything you do is naturally right by the mere circular justification that it was done by you.

Why do we need morality? Well, mobsters follow a code of honor. Merely following one set of rules or another is no guarantee of realizing benefit. And although Buddhism values the defense of life as the first and most important ethical prescription, the Mahayana (to which Zen and many other schools subscribe) gives “license to kill” in rare cases. When that death will prevent greater killing, that’s where the logic of Buddhist war begins.

Up to that point, it’s more or less okay. For the sake of a greater protection of life, it’s appropriate to kill one or two beings, and we avoid mentioning things like collateral damage or defending territories. But when a certain misunderstanding of Zen meets this doctrine, a kind of spiritual atomic bomb occurs.

All things considered, this doctrine, historically speaking, wasn’t even so abused—especially since it’s easy to consider the use of Zen by Japan in World War II also an abuse of Zen, not a mere participation of traditional Zen and Buddhism as complicit in all that. Particularly if we recognize that Japanese nationalism took on another character and intensity with the incipient studies of European philosophy, particularly German.

Moreover, Zen isn’t exactly an obvious, common practice for beginners.

Zen is often seen as an elite practice. Although it can benefit everyone who practices it, only a very small percentage of those who engage will reach an experience greater than satori, a brief flash of enlightenment. And, without the support of a qualified master—which has always been quite rare—it’s possible for the practitioner to suffer for many years (or even until death or through consecutive lives, from the Buddhist perspective) from what is called “Zen sickness.”

This is also why, traditionally, entering Zen practice is tough. There used to be a very strong screening process at work.

There are many types of Zen sickness, difficult experiences, and particular madnesses that arise from misguided or poorly executed meditation, but the type that concerns us here is a Zen sickness that was adopted by Japanese academia, after German romantic influence, as the “true Zen.” Basically, it’s a meditation practice that cultivates profound indifference, using the excuse of non-conceptuality as a mere detachment or spiritual coma—something more akin to romantic irrationalism than to Buddhism’s “reality as ethics.”

In a sense, this faux Zen has always existed or has always been co-opted by the powerful for militaristic purposes: it was the Zen that turned sutra passages into samurai code, promoting an extremely erroneous version of the notion of emptiness. Since everything is empty, you don’t tremble or hesitate when cutting off an opponent’s head. The Heart Sutra (Hridaya Prajnaparamita, a highly respected sutra in all Mahayana Buddhism, particularly Zen/C’han and Tibetan Buddhism), if misunderstood in a nihilistic way, can be appropriated as something like the two zeros of agent 007. The entire ideal of compassion, inseparable from emptiness—and emptiness as inseparable from form, ethics, materiality, practicality—is deliberately hidden to create extremely cold and effective warriors in the defense of feudal lords.

On one hand, warriors really need nerves of steel—and feudal lords need security. On the other hand, these absolutely mundane aspects began to be confused with the essence of Zen. And particularly confused after certain Japanese opened themselves to European ideas.

And so we have the romantic idea of rescuing a glorious past mixed with irrational romanticism—which projects onto non-conceptual Zen its extreme verve—and ultimately the cultivation of a “steel-like” determination, maximally indifferent. Karma? The future is just a concept, baby; the thing to do is just to clean the blood off the sword and move on.

And the lawless old West gets to be everywhere.

Add to that a dose of amphetamines (literally), and the result is the Blitzkrieg and the kamikaze. The master and inspiration for this practice of icy fury, in the samurai style, is the Emperor/Führer, who represents the spirit of the race, and war becomes something in which you act without feelings, without judgments, impassive as if in Zen meditation. It’s the meeting of Volksgeister (spirit of the tribe) with Zen sickness.

Entire nations suffered from this Zen sickness, and it wasn’t easy.

The absolute value here ended up being nationalism: as individuals, our feelings and empathy are irrelevant for warlike purposes. The Buddha’s tradition? Forget it—the axis is the emperor. If it’s not fair to blame German philosophy or Zen for the atrocities, it’s absolutely crucial to recognize the influence of both elements, distorted and mixed in varying proportions, in both Japan and Germany during World War II.

(And, don’t worry, we’ll get to Steve Jobs.)

Three Flavors of Zen Sickness

Buddhism generally uses a classification of basic afflictive emotions composed of three elements: aversion, craving, and indifference. War essentially used two types of Zen sickness, those linked to aversion and indifference. Of course, there was already craving in the conquest of new territories, but the Zen sickness most linked to craving would proliferate strongly only in contact with post-hippie American culture, 20 or 30 years later.

Zen arrives in the U.S. and becomes popular worldwide in its romanticized version, mixed with German philosophy, primarily through the work of D. T. Suzuki, but also through his disciple Alan Watts. What used to be sober, absolutely discreet, and restricted—those who wanted to experience Zen in the monastery often had to spend three days starving and thirsty at the gate before being accepted—became exposed in public lectures full of hype, in universities filled with cool, pot-smoking youth.

Although D. T. Suzuki is accused of being a nationalist and, therefore, in agreement with the militaristic stance Zen took and promoted during World War II, the more obvious accusation in retrospect is that he was not a Buddhist, never seriously practiced Zen, and didn’t really understand much about it. What he propagated was a diluted and popularized version of Zen established in Japanese academia (which had little to do with the living tradition of Zen preserved in its monasteries and more to do with folk tales about samurai).

The so-called “Kyoto School,” the same one that influenced militarism and Zen to converge during World War II, and which had mutual relationships not always openly acknowledged with Martin Heidegger—someone finally widely recognized today as a Nazist.

If the Zen of the Kyoto School in Japan was admittedly a mere influence—something philosophers appropriated according to their criteria but did not fully subscribe to—in the U.S. and the rest of the world, starting in the 1950s, D. T. Suzuki subverts the logic of influence and essentially creates a Zen rewritten by academic philosophy, with European influence. Zen, as a Newsweek report of the time aptly put it, to fascinate the post-war businessman.

Here, Zen is promptly and proudly dissociated from Buddhism, being more strongly linked, behold, precisely to the Japanese Volksgeist. But this independence of the Japanese spirit from Buddhism is offered to the “gentiles,” now victors of the war, as mere stripped-down aesthetics, nothing truly Japanese. Anyone who lives Zen as an experience will enjoy “no-mind”: an irrationalist object, against discourse—even though it is expressed in myriad books and quite popular lectures.

The world is too complicated, too mechanized, and the option is not to simplify or humanize the world, but to find an internal position of indifference that allows us to operate under any condition—and make the best of it. The “pure” individual of faux romantic Zen is one who annihilates their subjectivity in pure experience, with no regard for anything or anyone—since all these details are merely conceptual blemishes.

The benefit for the practitioner of such mental hara-kiri is not something in the future, but the present direct experience, untainted by concepts such as externalities or the feelings of others.

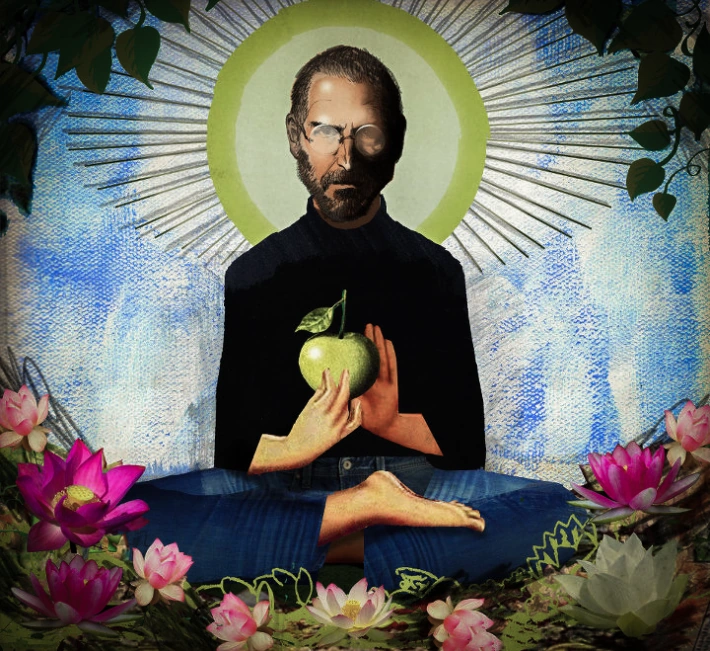

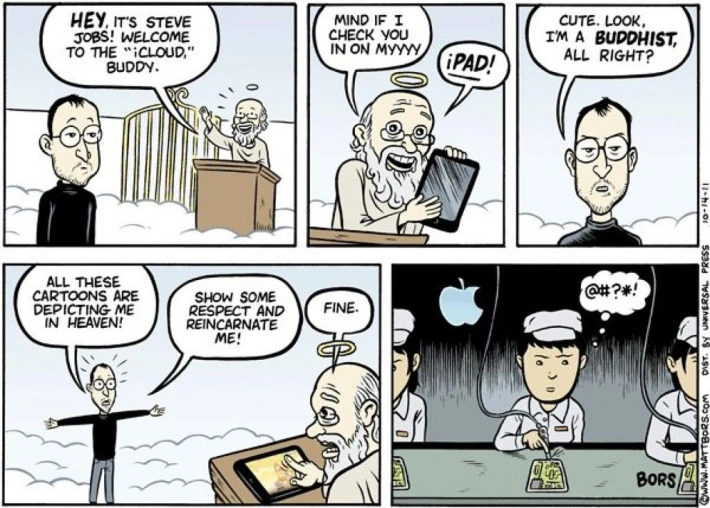

And it is at this moment that Don Draper—whose boss at the advertising agency already mixed Ayn Rand with Zen aesthetics—sits down to meditate and envisions the hippie Coca-Cola ad. The same moment when the young—we are finally here—Steve Jobs knocks on the door of a Zen master living in California to say he thinks he is an enlightened being.

Hype: Clean, Functional, Brilliant

The recent documentary about Steve Jobs, The Man in the Machine, emphasizes Jobs’ spirituality and his connection to Zen. The title is an ironic play on the idea of the “ghost in the machine,” that is, a critique of the dualist notion in the philosophy of mind—where a self-determined spirit could animate a deterministic body.

The names of Apple products, with their lowercase “i” at the beginning, represent the opposite: a product with which the user identifies at the most basic level—in other words, what is consumed is oneself, not just an extension of oneself or an idea of oneself in the form of a brand.

And add depersonalization to that, having to give money to a company in exchange for an identity! Other products degrade us by offering happiness; Apple went a step further—recognizing our depersonalization, it sells not just an idea of ourselves but everything we consider to be, that little mirrored object through which we filter our relationships with others, until it needs recharging.

One of the possible Zen sicknesses is confusing the Buddhist notions of emptiness and lack of identity with a mere absence, which the ego appropriates. Nagarjuna, in his Dispeller of Disputes, said, “Those who turn emptiness into a view [a thesis or object of knowledge or spiritual realization] are incorrigible.” In other words, what should be a strong recognition of interdependence and compassion becomes a form of profound isolation.

This is reflected in the lack of identity of a fanboy who seeks his personality in a mass-produced device and actively ignores the entire process of labor exploitation and environmental impact1In 2025, we can add that the user also ignores and thus ends up colaborating with inherently fascist artificial intelligence, the new oligarchic world order, technofeudalism, the enshittification of everything, acceleracionism and hipernormalisation. of his actions—which is a synergistic combination of simultaneous consumption and propaganda. This is without even delving into the neo-Luddite critiques of the information society and how it isolates us from each other under the pretense of fostering communication—of which Steve Jobs’ Zen disease would only bear partial blame.

However, effectively, consuming Apple is not just buying a product; it’s entering into a “subscription” to the culture of planned obsolescence, as well as penetrating an “ecosystem” where one becomes increasingly dependent on the company. We colaborate with fascist and totalitarian governments, with police brutality and with not owning our own minds. Thousands line up to participate in the dream and buy a little object that reifies themselves—not just as cool—and increasingly less as cool—but as finally I am someone.

We are slaves to our technomasters, and we seem to rejoyce in blindingly serving them.

And, in this case, the Volksgeist becomes the spirit of the company, copying the much-praised Japanese strategy of turning the company into a kind of sanctuary.

The irony lies in the often-pointed-out fact that revolutionaries end up appropriating the methods of the totalitarian regime they defeated. The advertising campaign for the launch of the Mac in 1984 was seminal in many ways—I, as a boy in Porto Alegre, was affected—perhaps I read 1984 for the first time because of Apple. The first joke is that the real enemy at that time was already Microsoft—IBM was on the verge of becoming relatively irrelevant. And thirty years later, Apple would be in the exact same position that IBM and Microsoft occupied: market leader, trendsetter, with a despicable corporate posture. 40 years later, step by step colaborating with a fascist government and helping as much as possible its accelerationist neo imperialistic project.

And of course, Big Brother was none other than a guy who used disabled parking spots in an unmarked vehicle—oh, how lovely these idiosyncrasies of the guru! Dressed in jeans and a basic black T-shirt, in pursuit of minimalism, expressing minimalism—the Edo period plastified with modernity—and surrounded by sycophants everywhere praising his powers of “reality distortion field.” Now that the hype has subsided a bit, testimonies are emerging that reveal Steve Jobs never outgrew the dirtbag behavior of pocketing a few dollars from his friend and the only true genius in Apple’s history, Steve Wozniak.

And Jobs’ achievements? Jobs was a great marketer and cheerleader, and in the area of sadistic (but effective) leadership, he truly revolutionized. Pure German romanticism—which at its root was against technology—appropriating technology as a spiritual value. Jobs wanted to change the world, but not just that: supposedly ideologically neutral, clean of theories like the Zen minimalism he espoused, he founded the first company that functions as a cult.

We must go beyond Apple’s highly interdependent advertising: they are selling a product to which you reduce yourself—which you recognize as your expression—directly coming from a legendary Yoda who preaches the freedom of the human spirit. And it’s not necessary, of course, to think he was actually a Darth Vader—we need to wake up from this reality distortion field that is mere propaganda. If we think churches that turn faith into a product are dirtbags, we must also recognize as dirtbags the companies that turn a product into faith.

“Success” is an elusive term to define. Edison was also a dirtbag, and some of his dirtbag behaviors follow us to this day in clumsy specifications for electrical power distribution. Just as the smart nerd knows the true hero was Tesla, not Edison, those who admire Jobs are unaware of Woz or Dennis Ritchie. However, if “success” is measured as “having great influence on the world,” it’s obvious that Steve Jobs was successful—no one would deny that. The question here is how much of this myth is mere propaganda, being aware we cannot visit the parallel reality where there was no Steve Jobs to know what would have happened. If measuring benefit in terms of great social changes is troublesome with centuries of distance, imagine right in the midst of them.

Yet it is certain that all the wonders of this era are ambiguous: each of them brought—according to the Buddhist doctrine of dukkha, unsatisfactoriness—corresponding problems. Some of them seem to be not just more suffering in general, but existentil threats.

And, meanwhile, the Zen disease continues in the culture, now in the form of meditation as a product. The mindfulness movement appropriates a technique of “non-judgment,” which in many ways carries the same problems of indifference toward suicides in Chinese factories that affected Jobs. So much so that it is applicable for shooters to concentrate better—exactly as in the time of the samurai. Not to mention the corporate environment itself, and particularly in Silicon Valley.

Meditation boxes on Amazon for the workers to boost productivity, climb the career ladder, and find a shallow sense of happiness while the world burns around them. Meditating not to understand the interdependent nature of reality, but simply to avoid taking pills and to keep helping the CEOs destroy the world with complete indifference.

Once more, following the example of the feudal lords of Japan, the argument becomes: “Let’s strip away the religious elements of Buddhism and sell just what we define as the core of it.” This promotes the meditation disease of cultivating impassivity. Of course, in certain situations, like rescuing a kitten from a burning building, impassivity can be a useful trait—provided it’s directed at the flames, not the kitten. Yet, this dispassionate detachment only makes sense within a broader context: the profound interconnectedness of all things. Unfortunately, this deeper context sounds too much like “religious talk,” and the whitewashed (or oriental-washed, “primitive”-washed) marketing of mindfulness as a product isn’t keen on embracing it. Instead, it sells a stripped-down, contextless version of meditation, divorced from its roots and stripped of its meaning.

Jobs himself could have encountered an authentic Zen master: root Zen, untainted by D. T. Suzuki or German romanticism, was already flourishing in California at the time—just as the bastardizations of the mindfulness movement were just beginning to take root. Yet, it became part of the public relations myth-making to exaggerate a Karate Kid-style connection to Asian teachings. Like many in California during his era, Jobs read Alan Watts and D. T. Suzuki, dabbling casually in romanticized notions of Asian enlightenment. The aesthetics of simplicity and the art of concealing complexity undoubtedly left a significant mark on his work. But how deeply he engaged with the tradition, or whether he truly meditated, is harder to ascertain. Judging by the outcomes, it seems that whatever contact he had with Zen was through its bastardized, romanticized, and decontextualized form—essentially, the fringe remnants of Japanese Zen, colonized and distorted by German thought.

Heidegger and the Kyoto School, much like the garbage collectors in Goiânia who stumbled upon a radiotherapy machine filled with Cesium-137 in 1987, breached the scraps of Zen and became captivated by the luminous, radiant substance they discovered. This substance, profoundly beneficial when applied correctly and in the right context, is devastatingly dangerous when mishandled out of ignorance. The thinkers of Kyoto and Germany, unfortunately, failed to grasp the true nature of what they had encountered—they were merely entranced by its allure. And so, they infected the cultural landscape with its radioactive indifference, spreading this toxic influence far and wide.

Six important words: this indifference still operates today as the essence of the technofeudalism that promotes the enshittification of everything, and which collaborates with the birth of the neofascism of hypernormalisation, in order to through capitalist realism ignore climate catastrophe and increasingly intensify inequality via accelerationism, which makes beings suffer today in the name of hypothetical futures.

This text was written in Brazilian Portuguese by Padma Dorje in October 2015.The author made some revisions and translated the text into English in March 2025.

Videos and texts on related subjects:

◦ Slavoj Žižek: Hipster Quackery (there is a Brazilian Portuguese version.)

Related films and documentaries:

◦ Steve Jobs: The Man in the Machine

◦ Rikyu

Related books:

◦ Popper, Karl. The Open Society and its Enemies: Hegel and Marx, book at amazon.com

◦ McMahan, David. The Making of Buddhist Modernism, book at amazon.com

◦ Page, Daizen Victoria. Zen at War, book at amazon.com

◦ The Zen of Steve Jobs, book at amazon.com

1. ^ In 2025, we can add that the user also ignores and thus ends up colaborating with inherently fascist artificial intelligence, the new oligarchic world order, technofeudalism, the enshittification of everything, acceleracionism and hipernormalisation.

tzal.org

tzal.orgSlavoj Žižek: Hipster Quackery

How substantial are Slavoj Žižek’s criticisms of Buddhism? Is there more to this prominent public intellectual’s counterintuitive--yet consistently entertaining--ramblings than mere showmanship?

IMDb

IMDbRikyu (1989)

Legendary tea master Sen no Rikyu is faced with his warmongering lord's unrealistic pretensions. // I love this movie. The feudal lord is so pathetic in his kitschness and absolute envy of Rikyu's artistic mastery. A lesson in Japanese classical aesthetics.

Current Affairs

Current AffairsCorporate “Mindfulness” Programs Are an Abomination

“When the individualized self bears sole responsibility for its happiness and emotional wellbeing, failure is synonymous with failure of the self, not external conditions.” — Ron Purser

TRICYCLE

TRICYCLEThe Dharma of Westworld

Reincarnation, no-self, and other Buddhist lessons from the popular HBO series. Have you been watching the first season of Westworld? Meditation teacher Jay Michaelson writes that the HBO show is "one of the most fascinating ruminations on the dharma" he's seen in American popular culture. // Well... I don't think so... but anyway, here's the link.