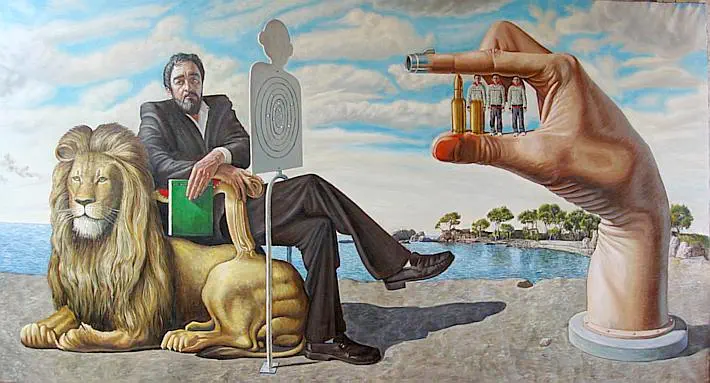

Understanding the Lion

(the in-joke of psychoanalysis)

On the possibility of Communication and Ethics: A little sketch on Wittgenstein's lectures on Aesthetics, Psychology and Religion”

What is to mean what we say? What is to understand what someone says? Is it possible for one to understand exactly what is being said by another? These are questions particularly relevant to psychology, yet they still stir profound philosophical perplexity.

Wittgenstein's famous phrase "IF a lion could talk, we would not understand him" implies his answer is negative, that is, there's no possibility of a completely public or universal language. To share a language is first and foremost to share a "form of life", that is, meaning arises from being together in a single landscape1In a sense there is an isomorphism between communication in general and the particular form of communication we call "in-joke", that is, linguistic situations where we amuse ourselves by our intimacy with a particular group or by putting those excluded in the position of perplex spectators of this intimacy., and not through a preexistent connection between language and facts or even established by convention2The first idea arises with Platonists, and the second is a bit more aristo telic..

A convention of any kind could only be established through an already occurring communication, creating an infinite regression. Furthermore, a preexisting (to sharing a landscape) connection would need some kind of absolute point of view, an underlying structure to reality (metaphysics), which would have to be a common ground. Notwithstanding, if this is the case, while we analyze this connection as one of the facts of the world and use language to describe it, we again fall in circular arguments—and this is a classic problem for philosophers, since any structural description of the world implies describing the possibility of this description, and so on. Thus our approach needs to be different, without denying or affirming this underlying structure: it is clear language works in this world.

Wittgenstein’s approach is to recognize this functionality of language and the inherent limitations to this functionality. In this way we have some limits of perplexity that will never be crossed, and this is not a impossibility of the world itself, or even of language, but of a simple incompatibility between “forms of life”.

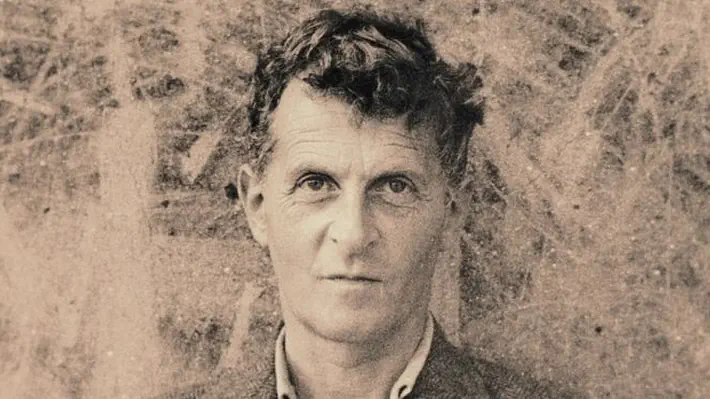

The idea of “forms of life” is still very much debated, and there is no consensus as to what Wittgenstein meant with it but in a very general way, as the peculiar insertion of someone or maybe a group in the world. A distinctive characteristic of Wittgenstein’s philosophy is its impenetrability: he himself said Russell, his mentor and one of the leading contemporary philosophers couldn’t understand him3As a matter of fact, Russell himself tells us about Wittgenstein’s PhD examination. He was standing behind the professors (Russel and Moore), and put a hand over each examiner’s shoulder and said “forget it, you’ll never understand”. That he received the degree is quite extraordinaire..

Wittgenstein therefore fits well the stereotype of the “isolated genius”, and it is not a surprise his interest in the possibility of communication4Wittgenstein found his closest pupils in a physician and an engineer (his own profession), people he advised not to follow philosophical “careers”. His philosophy didn’t seem to be written for philosophers (or at least not for the usual philosopher), and in many instances when philosophers tried unsuccessfully to interpret his philosophy, twisting it into “philosophish”, he would get very irritated. From this inscrutability and because philosophy deals with the limits of language, contemporary philosophers showed a great deal of interest in Wittgenstein, which was clearly not reciprocated..

In “Lectures and Conversations on Aesthetics, Psychology, and Religious Belief”, a work that came into being through notes took by his students at class (something that would certainly make Wittgenstein raise a brow) he finds similarities between those three seemingly so distant areas. Yet one would expect he wrote on the symbolism that may be shared or compared between them, but he stays within the clear limits of the paradoxical of the simultaneous private and public nature that they seem to exhibit.

One of his sisters was actually treated by Freud himself, so, for some time Wittgenstein thought of psychoanalysis as not much more than the latest vogue. However, when he actually came to read Freud, he did say it was one of the most interesting things around, and, oddly, not because he thought there was any kind of wisdom there. What was so peculiarly interesting in Freud’s writing that captivated Wittgenstein? The “Lectures” indicate Wittgenstein found in Freud a unique kind of aesthete!

Freud did something that seems profoundly wrong to me. He engages in what he calls dream interpretation [...] relates a dream which he describes as ‘beautiful’. A patient, after saying she had a beautiful dream, related it as coming down from a hill, seeing flowers and bushes, breaking a branch of a tree etc. Freud then presents what he calls ‘meaning’ of the dream. The grossest sexual nonsense [...]. For the non-initiated, a particular observation may seem harmless, but those who were initiated laugh inside, say, through hearing it. Freud states the dream is obscene. Is it so? He shows some relations between the oneiric images and certain objects of sexual nature. The relation he establishes is approximately of this kind. Through a chain of associations that naturally occur in certain circumstances, this leads to that, and so on. Is it the case that this proves a dream to be that which we call obscene? Clearly not; when somebody says obscenities, he doesn’t say something that seems harmless, and is then psychoanalyzed5Rhees noted “We don’t say somebody utters obscenities when his intention is innocent.” Freud called that dream ‘beautiful’, putting ‘beautiful’ in quotes. Wasn’t the dream beautiful? ‘Is it the case that those associations make the dream not beautiful? It was beautiful. Why wouldn’t it be?’ I would say Freud had deceived the patient. […] Why Freud gave such an explanation, after all? People could say two things: (1) He wants to exemplify everything that is good in a dirty manner, almost hinting he delights in obscenities. This is certainly not the case. (2) People have huge interest in the connections he establishes. They have a certain charm. It is charming [for some people] to destroy prejudices. […] ‘If we boil this man at 200º C, what will remain after the evaporation is some ashes etc. Here we have everything this man is.’ Stating such a thing can have its charm, but it would be deceitful, to say the least.6“Lectures & Conversations on Aesthetics, Psychology and Religion”, L. Wittgenstein, translated back to English from the Portuguese edition, italics added.

In this quotation Wittgenstein does not criticizes Freud for doing arbitrary symbolic connections as if it was science (he does that in other instances), but essentially points to the aesthetic connection of the “initiated”: “its charming to destroy prejudices”.

Wittgenstein himself, on the other hand, shared this aesthetic connection, and that’s maybe why he found Freud to be so interesting—not only because he recognized such thing and took a delight in this recognition, but we can also assume because he indulged in it, even being aware of the whole thing even more than the “initiated”7Wittgenstein had great fun with nonsense and detective stories, two forms of expression pretty much connected with the “destroying of prejudices” in their own ways: nonsense humor comes from an absurd relation shared by at least the author of the jest and his audience, and it breaks the “prejudice” of common sense; whodunit stories lead us to believe different suspects committed the crime, one after the other, only at the end revealing who it really was. Good stories are capable of surprising us, and this is, again, “breaking prejudices”. Hence my suggestion Wittgenstein not only understood why this “initiated” world came into being, he shared it..

The irony on this aesthetic taking on psychoanalysis is that Freud himself loathed it. When Dali started using the “paranoiac-critical method”, that obsessively reflected on what people would psychoanalytically interpret from his work, Freud—clearly fearing the transformation of his work in a mere freak curiosity—didn’t like it at all. 8Nevertheless, Freud liking it or not, it became a tradition that is still very much alive nowadays in the work of David Lynch, for instance—after going through Hitchcock it became pervasive, in a more subtle way of course, in almost any art form in the 20th century..

Wittgenstein’s philosophy is a peculiar one in that it almost becomes an anti-philosophy. But Wittgenstein is not only a ruthless critic of any fixation, his goal was to understand the limits of language. So it is in this sense that we can say the only way to understand the other is to share his/her/it “form of life”, that is, it is impossible to truly interpret or analyze the other, it is only possible establish a mutual relationship, that is, sharing the landscape. What we call interpretation or analysis (of a dream, of a person) is the imposition of some particular vision, essentially aesthetic in nature. Since ethics and aesthetics are the same thing for Wittgenstein, imposition implies, necessarily, an ethical problem.

Bibliography:

Ludwig Wittgenstein, Lectures & conversations on aesthetics, psychology and religious belief. Compiled from notes taken by Yorick Smythies, Rush Rhees and James Taylor. Edited by Cyril Barrett. Oxford: Blackwell, 1966.

Monk, Ray (1990). Ludwig Wittgenstein: The Duty of Genius. New York: Free Press, Maxwell Macmillan International

1. ^ In a sense there is an isomorphism between communication in general and the particular form of communication we call "in-joke", that is, linguistic situations where we amuse ourselves by our intimacy with a particular group or by putting those excluded in the position of perplex spectators of this intimacy.

2. ^ The first idea arises with Platonists, and the second is a bit more aristo telic.

3. ^ As a matter of fact, Russell himself tells us about Wittgenstein’s PhD examination. He was standing behind the professors (Russel and Moore), and put a hand over each examiner’s shoulder and said “forget it, you’ll never understand”. That he received the degree is quite extraordinaire.

4. ^ Wittgenstein found his closest pupils in a physician and an engineer (his own profession), people he advised not to follow philosophical “careers”. His philosophy didn’t seem to be written for philosophers (or at least not for the usual philosopher), and in many instances when philosophers tried unsuccessfully to interpret his philosophy, twisting it into “philosophish”, he would get very irritated. From this inscrutability and because philosophy deals with the limits of language, contemporary philosophers showed a great deal of interest in Wittgenstein, which was clearly not reciprocated.

5. ^ Rhees noted “We don’t say somebody utters obscenities when his intention is innocent.”

6. ^ “Lectures & Conversations on Aesthetics, Psychology and Religion”, L. Wittgenstein, translated back to English from the Portuguese edition, italics added.

7. ^ Wittgenstein had great fun with nonsense and detective stories, two forms of expression pretty much connected with the “destroying of prejudices” in their own ways: nonsense humor comes from an absurd relation shared by at least the author of the jest and his audience, and it breaks the “prejudice” of common sense; whodunit stories lead us to believe different suspects committed the crime, one after the other, only at the end revealing who it really was. Good stories are capable of surprising us, and this is, again, “breaking prejudices”. Hence my suggestion Wittgenstein not only understood why this “initiated” world came into being, he shared it.

8. ^ Nevertheless, Freud liking it or not, it became a tradition that is still very much alive nowadays in the work of David Lynch, for instance—after going through Hitchcock it became pervasive, in a more subtle way of course, in almost any art form in the 20th century.

tzal.org

tzal.orgA Review of Hema Hema

The movie by Khyentse Norbu in the words of your favorite webkeeper Padma Dorje.

YouTube

YouTubeWittgenstein - Sea of Faith

Part one of a two-part excerpt on Ludwig Wittgenstein, focusing on his sense of religious belief. Taken from the 1984 BBC documentary, Sea of Faith.